The quaint Northern California coastal town of Mendocino exerts a powerful attraction on artistic and educated people. Preserving the charm of what appears to be a 19th century New England village, Mendocino seems a relic of a quieter, gentler past.

“Now that I am an old man... I'm still getting an education.”

My father, Alex Mendosa, however, grew up in Mendocino as the 19th century was turning into the 20th. To him the town was instead a raw frontier village that he simply had to leave to become an educated person. More than anything else he wanted an education, and that was something unavailable to him in Mendocino.

The odds were long against anyone from Mendocino graduating from college in the early part of the century. And even today if you drop out of school after the eighth grade, the odds are distinctly stacked against you.

Dad faced both of those problems and somehow beat those odds. Not until he was 21 did he even start high school. Born in Mendocino in 1899, he went to work in the family store when he was 10.

Mendocino Today

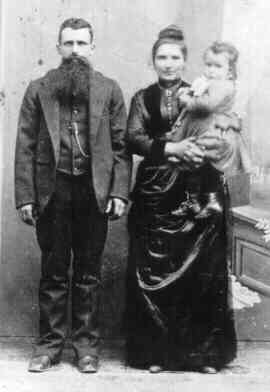

The youngest of eight children of unschooled immigrants, right from his birth Dad was an unlikely candidate for a university education. Then, on June 13, 1902, even before he began school, his chance for an education practically disappeared. Dad was 3.

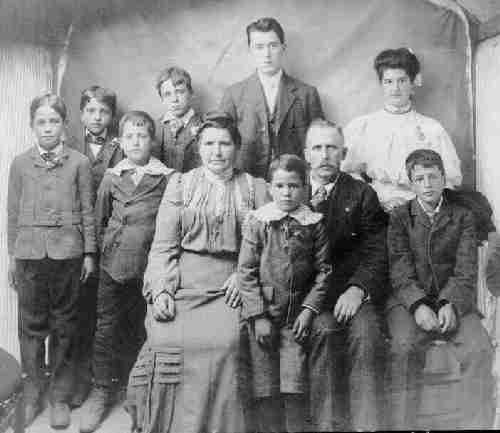

His father Frank, who was, according to family records, born Francisco José Mendonça on March 15, 1851, in the Lajes parish on the tiny island of Flores in the Azores off the coast of Portugal, was a mill hand in the Mendocino sawmill when my father was born.

As a teenager my grandfather worked his way to America on a whaling ship. He immigrated to the United States in 1867, according to the 1920 Federal Census. He is listed in the 1880 Federal Census as a single lumberman working in the Caspar area, which is about five miles north of Mendocino. This census lists him adjacent to another young lumberman named Antone Lopes, which means that they probably shared living quarters. They were probably good friends and in fact bought some land on Little Lake Road in Mendocino in February 1882, according to Eleanor Sverko's Early Portuguese Families of the Town of Mendocino (Privately printed, 1995). That connection may explain how my grandparents met.

António (Antone) Lopes was born in December 1854 on the island of São Jorge in the Azores. His sister, Isabel Jacinta Lopes, was my grandmother and was born in the village of Carvalho of the Calheta parish on São Jorge on December 16, 1861. She arrived in 1887, according to the 1920 Federal Census. On October 26, 1887, my grandparents were married in Mendocino. I consider myself fortunate to have met her and my great-uncle Antone in 1938 when my father took me to Mendocino. She died the next year, and Antone died in 1946. My grandfather had passed away in 1924, before I was born.

My grandfather came to Mendocino in 1871 and my great-uncle Antone arrived two years later, according to The Portuguese in California by August Mark Vaz (Oakland: I.D.E.S. Supreme Council, 1965). Mr. Vaz wrote that, "Early pioneers in Mendocino included Antonio S. Lopes (S. Jorge), who arrived in 1873... In 1871 from Flores came...Frank J. Mendonça."

Dad's Parents, Francisco José Mendonça and Isabel Jacinta Lopes Mendonça, with my Uncle Tony, about 1890

At the turn of the century my grandfather had come in from the woods and was working in Mendocino's sawmill when the accident happened that changed his life. "He was on a platform that moved back and forth and sawed the logs," Dad recounts. "A chain got wrapped up in his right arm and tore it off." With no savings or social security and a large family to support, my grandfather was suddenly out of a job.

Unable to do the hard physical labor he had done all his life, my grandfather became a businessman, because there wasn't anything else he could do. But the saloon he opened got off to a slow start. The only customer on the first day purchased a 5 cent glass of beer, according to the recollection of Dad's brother Bill. My grandfather added food, and called the business a chophouse. A contemporary advertisement tells of "good lunches, oysters and tamales."

It was to no avail. In July 1909 Mendocino voted for prohibition, putting the town's 14 saloons out of business.

In October 1909 my grandfather's saloon was reborn as Mendosa's general store. Today, more than 90 years later it remains the Mendosa family business and a piece of Mendocino history.

The Family Store Today

Dad remembers working there from the time it opened. "I started working in the store doing odd jobs, delivering packages, grinding coffee," he recalls. "I had no time for play," he says. "I got through school and I went to work." Saturdays and Sundays were regular work days too.

Everything came by steamer from San Francisco. Dad and his brothers hauled most of the merchandise up the cliff to the store. The other children taunted them with names like "Mendosa's jackasses," Dad remembers.

Not until 1918 was the family able to afford a horse and wagon. When greater prosperity came in 1919, they were able to buy their first horseless carriage, a Model T delivery truck. Cars were so rare those days in Mendocino that it wasn't until he was 13 that he saw his first car, a Studebaker.

Although only 130 miles northwest of San Francisco, Mendocino in the early part of the century was isolated from the rest of the world. Electricity didn't arrive until 1902. Moving pictures made their local debut in 1911. Paved roads were non-existent. The only ways to reach the wider world were the occasional ship and a train that served the nearby village of Fort Bragg.

Click Image To Enlarge

Dad Rides a Bike next to Mendosa's Wagon Drawn by Babe and Driven by One of His Brothers

After graduating in 1913 from what was then called a "grammar school," Dad went to work full time in the store. "I gave all my earnings to help the family," he recollects. "My father in turn gave me what money I needed for personal use."

Dad dreamed of being a high school teacher, the sort of person who commanded respect in the little community. The high school principal, Eugene Gauthier, was a regular customer of the store and encouraged that dream. But World War I put Dad's plans on hold.

"Between 1916 and 1917 my five brothers living in Mendocino were called into war service," Dad recounts. "My father, my sister Mary and I kept the store operating."

When his brothers returned home at the end of the war in 1918, the family no longer required Dad to work at the store. So his father sent him to the sawmill instead—the same mill where his father had lost an arm.

"My job was on the sorting table," Dad says. "Lumber came out on the sorting table, and it was marked. Some was marked R to resaw, and I was to move that lumber into cars and bins. It was work anyone could do, but it was hard work."

It was also low paying work. And the hours were long. "I remember working 10 and 12 hours a day, more likely 12. It was a rough life."

Still, he kept the dream alive. His fellow workers in the mill gave him no encouragement. "I was talking to young men of my age at that time, and telling them what I planned to do," he says. "And they said, 'You're crazy! You'll be an old man when you get out of school.' They didn't realize, of course, that if I didn't go to school, I'd be just as old," he says with a laugh.

Finally, more than six years after dropping out of school, in 1920 he was able to continue his education. But to do it he would have to leave home. "If I went to high school in Mendocino," he says, "I'd have to work until 9 at night, and I wouldn't have had time to study."

For the first time in his life he would see a city. And what a city it was—San Francisco, then certainly the most cosmopolitan city on the West Coast. "I was flabbergasted," he says of the city. "I was very much a country kid." Nevertheless, going to high school was still a dream. Instead, he detoured through a business school.

"I didn't have any money," he says. "But there was a chance for me to get away from Mendocino to live very inexpensively with my brother Tony and to go to Heald Business College." Tony had a job at a florist shop in downtown San Francisco, just a few blocks from Heald.

"I went there with one thing in mind," Dad recalls. "After I graduated from Heald I was coming back to Mendocino to have my credits evaluated by Mr. Gauthier, the school principal." And that's what he did, some 10 months after entering Heald.

With credits equivalent to three high school semesters, Dad finally attended his first high school class in early 1921. Again he would have to leave home. His destination this time was Oakland High School.

Why Oakland? "It was closer to the University of California," Dad says, "and that's what I had my eyes on." By taking a heavy load of courses he was able to finish in one and one-half years in 1922, even graduating with honors.

Nevertheless, he barely made it. He financed his high school years with odd jobs, like making beds in the rooming house he stayed at. "I ran myself ragged," he says.

In fact, the pressure was too much, and he dropped out of school again—but this time only briefly. "I wasn't very rugged at that time—never have been for that matter—and I just about gave up," Dad recalls. "I stayed away for several days."

Sue Dunbar, the Oakland High dean of women, had taken an interest in him. "That's when [she] came to my rescue. She came to where I was living and encouraged me to go back to school, which I did."

Photo courtesy of Bev Shulster and the Oakland High School Memorial site.

He went right on to college. "I couldn't afford to go to the University of California at Berkeley," he says, "but I went anyway—without money and working." His job, waiting on tables at Phi Kappa Tau fraternity, exposed him to social graces unknown in Mendocino.

Later, he became the fraternity's first employee ever invited to become a member. He became financial secretary of the chapter, which provided him with board and lodging.

A devastating fire ravaged Berkeley in September 1923 as Dad began his sophomore year at UC Berkeley. The fire destroyed almost 600 buildings and left 4,000 people homeless. The fraternity brothers, Dad among them, went out together to help save what houses they could.

By a strange fluke, one of the houses they saved was Sue Dunbar's home. "She was the teacher who helped me tremendously while I was at Oakland High School," Dad says. "It was a great joy to me, because she was there." It was one of those freak things, he says, a coincidence.

During summer vacations Dad took the best paying work he could find. One summer it meant icing fruit cars near Brawley in the Imperial Valley. Without air conditioning in those days, the temperature in the desert soared into the 120s. But it paid "good money," which "at that time was 50 cents an hour," he recalls. "And the hours were long, as many as 20 hours a day, including Saturdays and Sundays."

Graduating from UC Berkeley in 1926 with a B.A. in history and social science, Dad had not yet completed his education. "I returned to the University of California for my fifth year to obtain a general secondary teaching credential," he says.

His first teaching job was at Mariposa High School. He was also the baseball coach. Dad is still proud of his team's undefeated record in the only coaching job he ever had—five or six wins and no losses. Subsequently he taught at Chico High School before moving to Southern California in 1931, when he joined the faculties of Santa Monica High School and College.

My Father, about the time he Moved to Southern California

But before moving to the Southland, fate had one more milestone for him to pass. While attending a continuing education course during the summer of 1931 he met a pretty teacher from Michigan who was spending the summer at the sorority house next door to his fraternity. That woman was Eva Ash, and early the next year they were married. The marriage lasted 54 years until she passed away on June 8, 1986.

My Mother, Eva Ash Mendosa, in her Early 20s

The University of Southern California awarded Dad a master's degree in history in June 1933. At that point he had finally completed his formal education. He was 34, not quite the "old man" his co-workers in the sawmill had predicted he would be.

My Loving Father Holds Me, 1936

In the late 1950s Dad retired from teaching after 29 years.

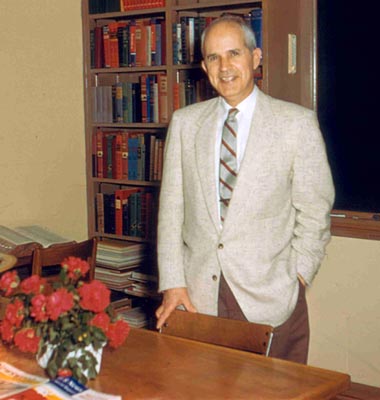

Dad in his classroom. According to the calendar on the wall (which I cropped out of this print) it was May 1957 when this picture was taken. Strange, because it is one of my slides. But I never left Europe between 1955 and 1959.

My parents visited me for several weeks after I moved to Washington in 1961.

My mother and father on the steps of the White House about 1963.

My father passed away quietly on May 18, 1996, just one week before he would have been 97.

A condensed version of this article appeared in O Progresso, the newsletter of the Portuguese Historical and Cultural Society in Sacramento, California, December 2000, pp. 5-6.

![[Go Back]](back-new.gif) Go back to Home Page

Go back to Home Page

Last modified: April 22, 2003