When Sonja Fuller and her husband Bill moved back to Dallas in 1990 after living in Austin, her diabetes got out of control.

Insulin changed my life.

"It seems like every three months we had a death in our family, and my husband lost his job," she recalls. "Everything was stress, stress, stress, and my blood sugars just skyrocketed."

Almost 20 years ago Fuller, now 59, was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes—formerly called adult-onset diabetes. At first she was able to control her blood sugar with diet and exercise alone. Then, her doctor prescribed oral drugs.

Eventually, she was taking three kinds of pills for diabetes. "I felt terrible," she says. "I couldn't do anything but sit in a chair and fall asleep."

Her fasting blood sugars were far too high—195 to 200 milligrams per deciliter. To maintain good control they shouldn't have been more than 115 or 120.

A friend of hers who works at Baylor University Medical Center was concerned. Her friend showed her an employee newsletter that told about a new "Team Diabetes Self-Management Training Program" at Baylor Health Care System.

"It is a program of diabetic education," Fuller says. "You work with dietitians and nurses. They recommended that I see an endo and go on insulin."

An endo is an endocrinologist, a specialist in the treatment of diabetes. Like many people with diabetes, Fuller's previous doctor was not a specialist in the disease.

The endocrinologist, Dr. Priscilla Hollander, switched Fuller to insulin in October. "It absolutely changed my life," she exclaims. "My attitude is so different that I am not even the same human being. I am so full of energy!"

The reason why Fuller is feeling so good is that her blood-sugar levels are finally under control. "Yesterday all day long they were awesome—78 fasting, 62 at lunch, 103 before dinner, and 78 at bedtime."

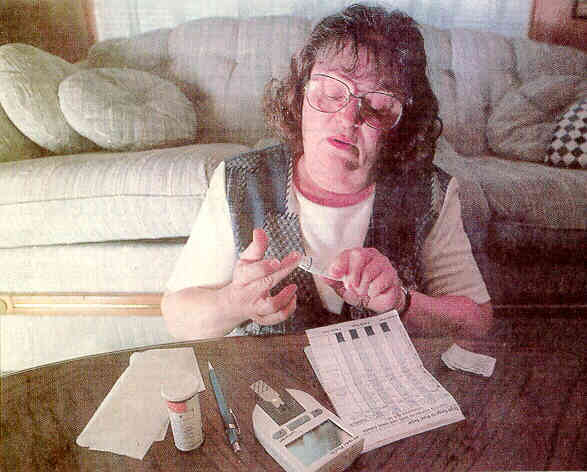

Sonja Fuller tests her blood sugar at home

While Sonja Fuller is finally controlling her diabetes—rather than the other way around—many people here aren't. Sixteen million Americans have the disease, according to government statistics.

In Texas alone 1.1 million people have diabetes, according to Errika Flood, regional director of programs and communications for the Irving-based southcentral region of the American Diabetes Association (ADA). One-third of these don't even know it, she says.

Nearly half of all Americans with type 2 diabetes who take oral medications to treat the disease have blood-sugar levels well in excess of accepted clinical guidelines, according to a random telephone poll this summer of 500 people with type 2 diabetes. Roper Starch Worldwide conducted the research for Eli Lilly and Company, America's top insulin manufacturer.

A blood-sugar level of 140 milligrams per deciliter is the the point where the ADA says you should take action to reduce the risk of complications. With 44 percent of people with diabetes reaching levels above 140, the survey suggests that many patients need to change their therapy. Other research shows there are about one million patients with type 2 diabetes whose blood-sugar levels are that high. And that's not counting the millions more who aren't aware that they have the disease.

To reach these people, Lilly just kicked off a national diabetes action campaign called "The Search for the Missing Millions." The campaign will work with local health officials and diabetes groups in 16 cities to help get these millions screened, diagnosed, and treated.

Spokespeople for the campaign are Nicole Johnson, Miss America 1999, and Howie Long, network football commentator and former NFL superstar. They plan on taking the campaign to Dallas in February. Meanwhile, you can call (800) 708-7001 for a brochure on the campaign.

While Johnson herself has diabetes, Long is involved because he saw how uncontrolled diabetes devastated his family. "The message that we are trying to get out is let's get a bead on this before the complications began," Long tells the Dallas Morning News. "The symptoms of diabetes—blurred vision, fatigue, urinating through the evening, thirst - often pop up late."

When these missing millions are found, they can begin to control their diabetes. But they can't cure it. There is still no cure for the disease.

"If you look at the discovery of insulin in the 1920s, it was probably considered a cure by people whose lives were saved by it," says Deb Butterfield, executive director of the Insulin-Free World Foundation.

"But it soon became apparent that insulin wasn't a cure. The evolution now to transplantation as a 'cure' leads us to a more perfect place, but it is still clearly not a cure. It is still a form of treating diabetes. It requires ongoing immunosuppression drugs."

Butterfield has the nearest thing to a cure—a transplanted pancreas to replace hers, which was no longer working. In fact, she has had two transplants, since the first one failed.

About 11,000 people have had pancreas transplants, Butterfield says. The success rate is about 80 percent.

Besides the need to take drugs to prevent the body's rejection of the foreign organ, other limitations of pancreas transplants are the cost—about $60,000—and the limited supply. About 5,000 pancreases become available a year through the organ allocation system, she says.

A less-invasive operation is the transplantation of just the cells of the pancreas that produce insulin. Worldwide, about 300 people have had these islet-cell transplants. But only 10 percent of these patients have been able to avoid taking insulin shots for at least a year, Butterfield says.

Meanwhile, Sonja Fuller has no interest in a transplant. "Not only is it expensive and invasive, but there are the drugs that you have to take. I take enough drugs as it is."

This is an unedited version of the article that originally appeared in The Dallas Morning News, December 7, 1998.

![[Go Back]](back-new.gif) Go back to Home Page

Go back to Home Page

![[Go Back]](back-new.gif) Go back to Diabetes Directory

Go back to Diabetes Directory